Even though securities class actions were a powerful tool for addressing corporate abuses, as were class actions more generally, frivolous cases often grabbed the headlines. Critics argued that class actions were too burdensome for corporate defendants. Unsurprisingly, many of the corporate interests who were held accountable by class actions joined in the criticism.

The worry over meritless class actions was compounded by a fear that companies facing class actions could be extorted into agreeing to a settlement. If a class action was not dismissed by the judge, the process of discovery would begin, which meant the plaintiffs could demand documentary evidence from the defendant. Defending companies sometimes found it cheaper to agree to a settlement than to proceed with litigation.

Another problem, which was specific to securities class actions, was that investors (or, more accurately, the plaintiff law firms) often rushed to be the first to file a securities class action when the price of a security went through a significant decline. This was known as the “race to the courthouse.” If a small investor was the first to file a class action they could be “in control” of the litigation, which really meant that the law firm representing that small investor would control the litigation—even against the wishes of investors who had suffered far more economic harm.

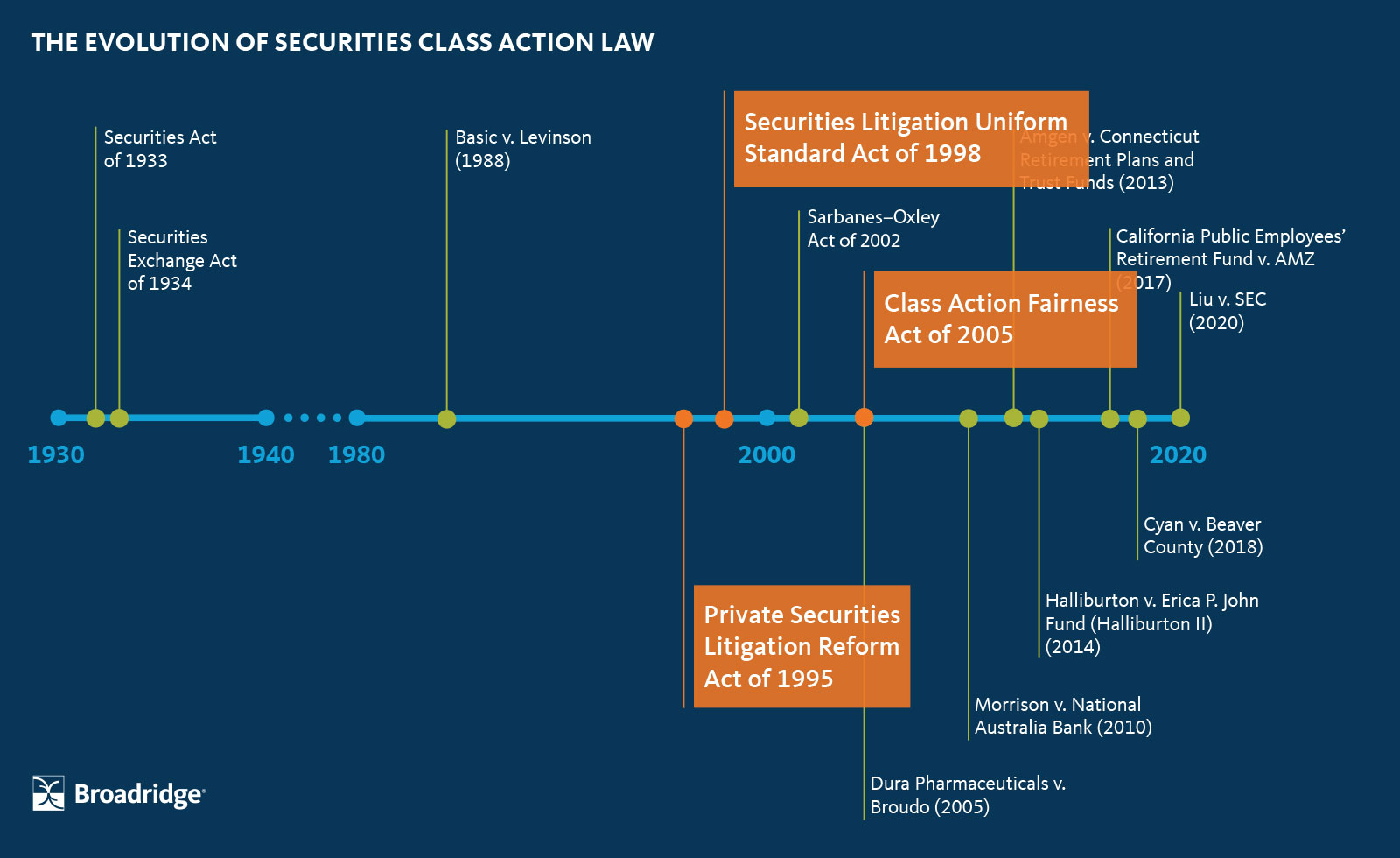

Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995

Impact

- Created higher pleading standards for securities class actions.

- Eliminated the “race to the courthouse” by directing courts to look at the person or entity with the most economic harm rather than the first to file, which had the effect of encouraging institutional investors to lead securities litigation.

Congress became sympathetic to concerns about the excesses of class actions, especially after the Republicans won majorities in both houses of Congress in the 1994 election. Congress decided to begin by focusing on securities class actions in particular, and to create new requirements that would promote the integrity of these cases. This led to the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995 (PSLRA).

The PSLRA placed limits on securities class actions in federal court. The PSLRA’s focus on federal court was thought to be sufficient since that is where most securities class actions were litigated at the time.

The PSLRA raised the threshold for filing a securities lawsuit, imposing more stringent pleading requirements on plaintiffs. This meant that securities class actions of questionable merit could more easily be dismissed before expensive litigation began. The following are some of the new pleading requirements that the PSLRA imposed:

- Plaintiffs must state in specific terms what misleading statements have been made.

- Plaintiffs are required to claim that the defendant knew the statement was misleading. A company cannot be sued if it is only claimed that an executive negligently but unintentionally said something misleading.

- Plaintiffs are required to claim that the statement caused them losses. This means that a statement that was misleading but not actually relevant to the price of securities cannot be the basis of a lawsuit.

The PSLRA also addressed the “race to the courthouse” problem. It required the first plaintiff filing a securities class action to notify other investors, who had 60 days to apply to be the lead plaintiff. The investor with the greatest financial interest in the case was usually allowed to be lead plaintiff, unless the judge found that for some particular reason that they were not adequate to lead the class. This usually meant that large institutional investors controlled the litigation and selected lawyers for the class.

Securities Litigation Uniform Standards Act of 1998

Impact

- Required class actions based on Rule 10b-5 and fraud on the market to be brought in federal court.

- Stopped a trend towards filing securities class actions in state courts to avoid the heightened requirements of the PSLRA.

In 1995, the PSLRA had created more stringent requirements for securities class actions, but it only applied to federal courts. States had their own laws against securities fraud. While securities class actions in state courts had previously been rare, more plaintiffs began filing class actions in state courts to escape the requirements of the PSLRA.

Congress addressed this trend by passing the Securities Litigation Uniform Standards Act of 1998 (SLUSA), which had the explicit purpose of preventing plaintiffs from evading the federal requirements and frustrating the objectives of the PSLRA. SLUSA steered securities class actions from state courts into federal courts, and into the more stringent requirements of the PSLRA.

For most securities fraud class actions that can be brought under federal law or state law, SLUSA requires that they be brought under federal law, where the PSLRA applies. This applies to class actions consisting of over 50 class members that are covered by SLUSA’s requirements. Most importantly, claims based on Rule 10b-5 and fraud on the market, which are the most common securities class actions, are covered by SLUSA’s requirements and therefore must be brought in federal court. If such a class action is brought in state court, the defendant can remove it to federal court.

Strangely, SLUSA was not very clear on whether Section 11 claims could continue to be brought in state court. This caused a great deal of confusion over the two decades following SLUSA. Finally, in Cyan v. Beaver County (2018) the Supreme Court determined that SLUSA permits class actions that consist solely of Section 11 claims to be brought in state court1. This decision and its implications will be the topic of a future article.

Class Action Fairness Act of 2005

Impact

- Expanded federal jurisdiction to cover most class actions of significant size—not just securities class actions.

- Reduced the ability to litigate class actions in state courts, which tend to be a friendlier forum.

The PSLRA and SLUSA placed significant constraints on securities class actions. But the possibility of frivolous class actions continued to be widely discussed, and the concern was not limited to securities law. By 2005, the Republican Congress generally viewed class actions with skepticism and decided to take broader measures to rein them in.

This led Congress to pass the Class Action Fairness Act of 2005 (CAFA). CAFA limited the ability of plaintiffs to file class actions in state courts, which are generally viewed as friendlier forums for class actions, and which offered plaintiffs the opportunity to pick the most favorable state in which to file a class action. Where SLUSA had been an effort to push securities class actions to federal courts, CAFA was an effort to do so for all other class actions.

Specifically, CAFA expanded the federal government’s diversity jurisdiction over class actions. Previously, there had to be at least one individual plaintiff suing for at least $75,000 for a class action to be brought in federal court, which excluded classes consisting entirely of small claimants. Now, the amount in controversy had to exceed $5 million, but that amount could be aggregated among the entire class. CAFA also relaxed the requirement for geographic diversity, allowing class actions to be brought in federal court as long as at least one class member, including an unnamed class member, was from a different state than at least one defendant.

CAFA specifically did not apply to securities class actions because Congress assumed they had already been addressed by SLUSA. However, CAFA was another clear message that Congress intended to move the bulk of class action litigation into federal courts, and to significantly limit any possibility of frivolous class actions.